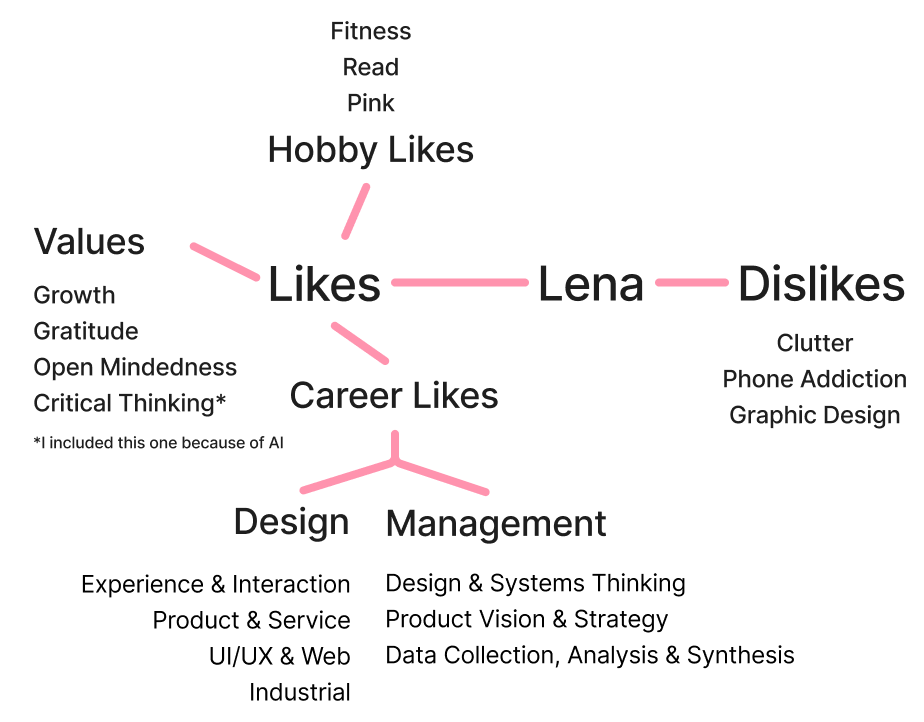

[SHOOKS]

Description

This undergraduate capstone project is a case study of an unorthodox home organization product and its implications. It involves the creation of "shelf-hooks" called shooks, which rely on walls, corners, and other shooks to form an organizational system. Deeply rooted in my passion for systems and home products (yes, I love containers), the project explores nonlinearity and organization psychology through the lens of systems design.

Skills

Industrial Design

Systems Design

Qualitative Research

Market Research

3D Modeling & Printing

Interviewing

Photoshop

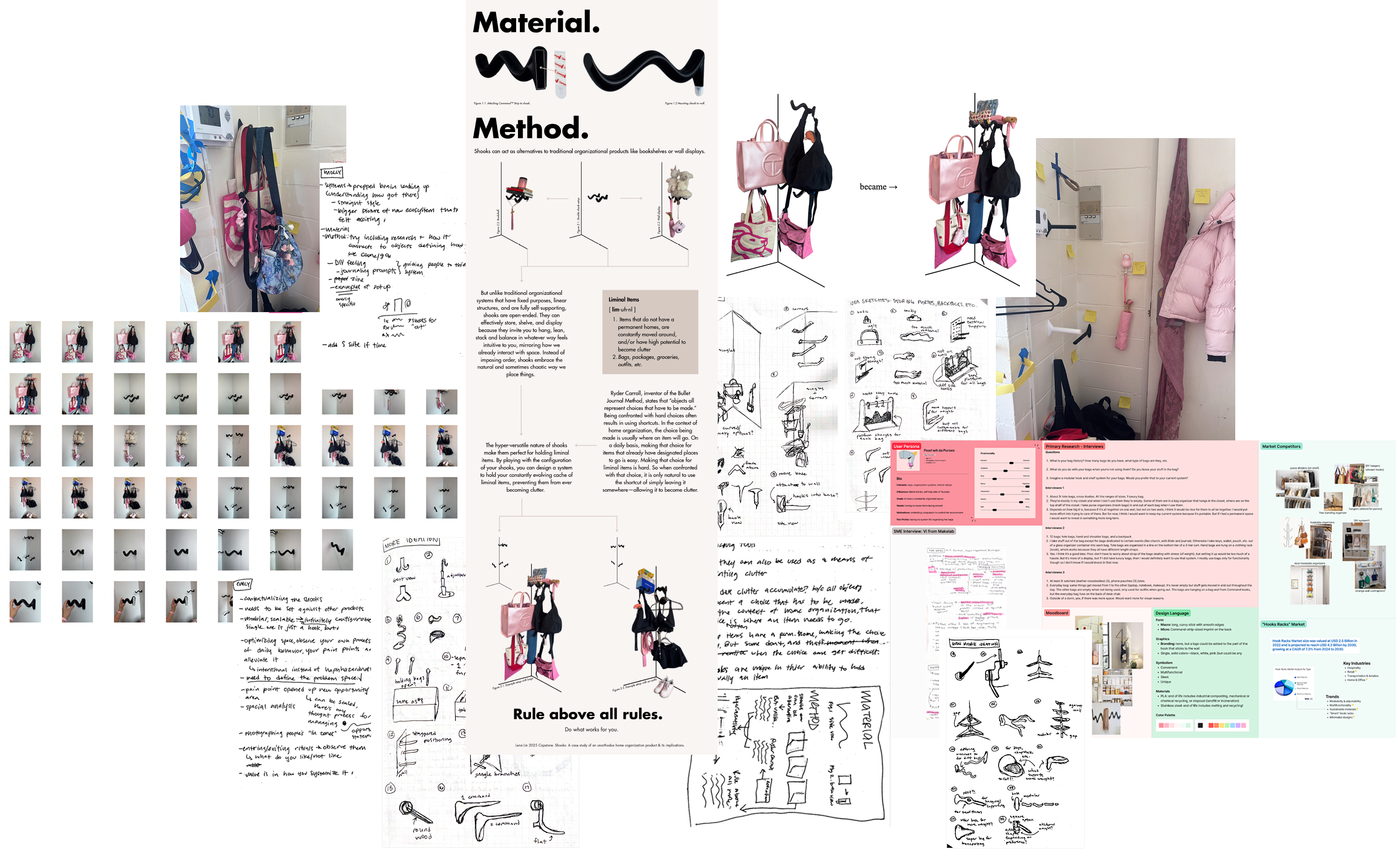

[NOTION INC. GROWTH STRATEGY]

Description

This case study on Notion Inc. (1) explores various growth opportunities and (2) recommends a winning strategy through a design strategy lens. It features frameworks and tools such as Jobs To Be Done, “How Might We” statements, business scorecards, a lovable.ai marketing site prototype, a business model canvas, etc. This case study was ultimately a high level practice in applying creativity and design thinking principles to a non-design field.

Skills

Design Stategy

User Research

Market Research

Data Analysis & Synthesis

Business Model Design

AI Prototyping

Presenting

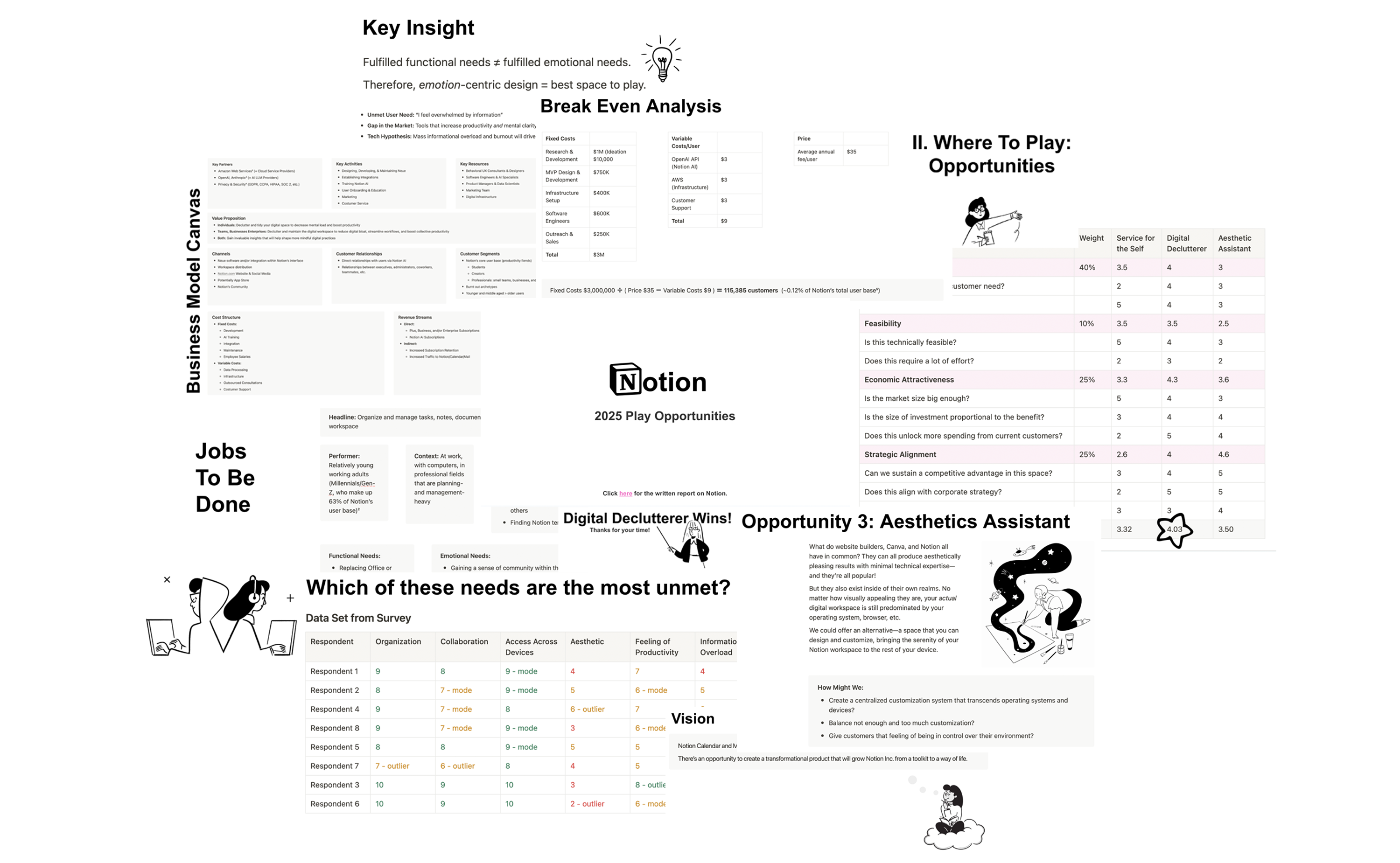

[THE GREY ZONE]

Description

Teammates: Nayan Sarma, Yilin Wang

Problem Statement: "How might we foster less antagonistic interactions between the pro-life and pro-choice movements?"

Goal: Design a service that addresses at least two of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Key Insight: While people were often open to talking about abortion—especially with their close friends or family—they (1) did not want to start a debate and (2) did not feel as though they were in the right environment to hold a proper conversation.

Solution: A simple card game called “The Grey Zone,” with four main components:

- A physical and/or digital invitation to the game

- A set of notepad and pencil

- Prompt cards with questions about abortion sorted into three levels of difficulty

- Emotion tokens, which are small characters with faces that portray 5 primary emotions

Players take turns to answer prompt cards, and as they respond, other players can place emotion tokens down, and later reflect on their reactions and reasoning.

Impact: By playing “The Grey Zone,” players are offered an easy “excuse” to bring up the topic of abortion with loved ones, collaboratively create a safe environment to discuss, and gain a deeper understanding of opposing perspectives and experiences.

Skills

Service Design

Interviewing

Brainstorming

Data Analysis & Synthesis

Rapid Prototyping

User Testing

Figma

Presenting

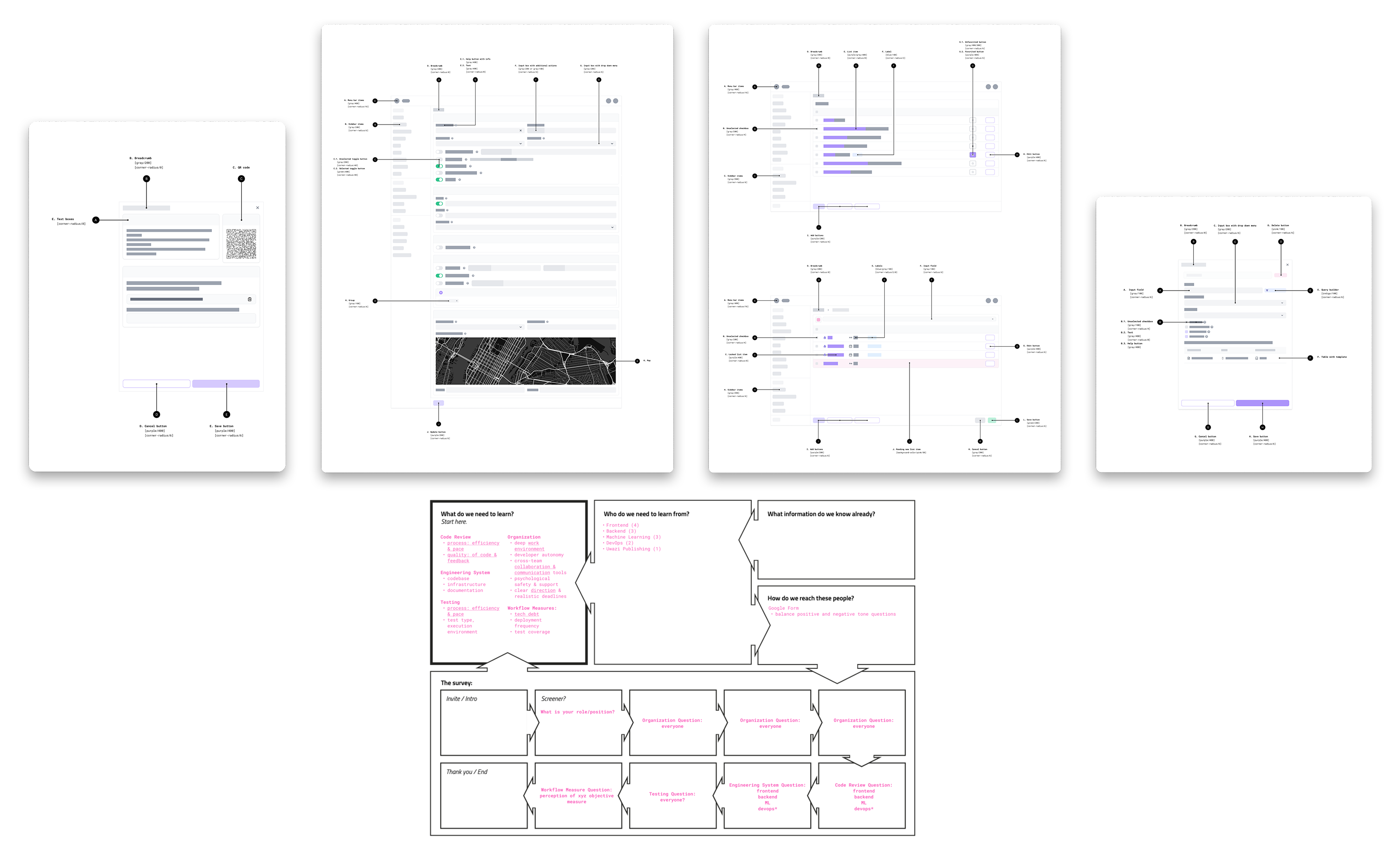

[HURIDOCS]

Description

During the summer of 2023, I was sponsored by the NYU Social Impact Changemaker Fellowship to work as a design intern at HURIDOCS, the nonprofit behind Uwazi, a database web application for documenting information on human rights violations.

Projects and Impact:

- An Uwazi "Visual Language to Plain Language" breakdown guide—preventing dissonance between Uwazi's designers/developers and customers who may not be tech-savvy enough to navigate the interface with ease.

- An Uwazi UI system map—comprehensively defining Uwazi's UI assets and software structure, acting as a style guide for internal reference.

- A Developer Experience (DevEx) survey—introducing the first solely developer-focused practice to gauge employee satisfaction, and setting the foundation for long term workplace health check-ins.

Skills

Design Research

Design Documentation

Figma

Visual Design

Product Design

Survey Design

Presenting

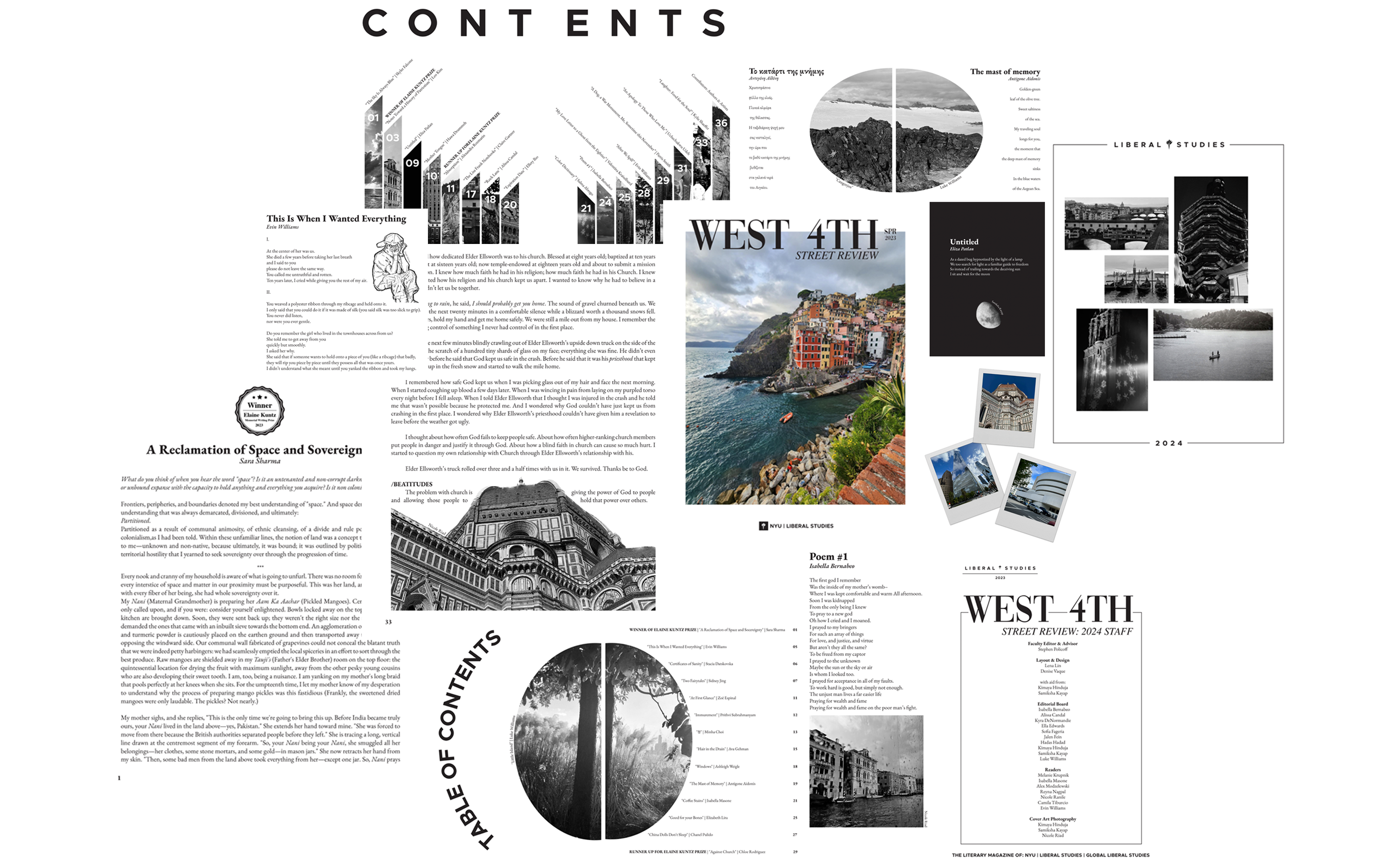

[WEST 4TH STREET REVIEW]

Description

In 2023 and 2024, I was one of two principal designers for the West 4th Street Review, an NYU Global Liberal Studies & Liberal Studies Core literary magazine.

My co-designer, Denise Vaque, and I, brought the magazine from conceptualization to print, which primarily consisted of:

- Editing and compiling the content (writing and photography)

- Designing each spread's layout

- Creating the magazine in Adobe InDesign

Afterwards, I also designed a long term system to systematize the annual designer recruiting process and lower the turnover rate. I onboarded and mentored two additional designers.

Skills

InDesign

Photoshop

Adobe Illustrator

Layout Design

Editing

Mentorship